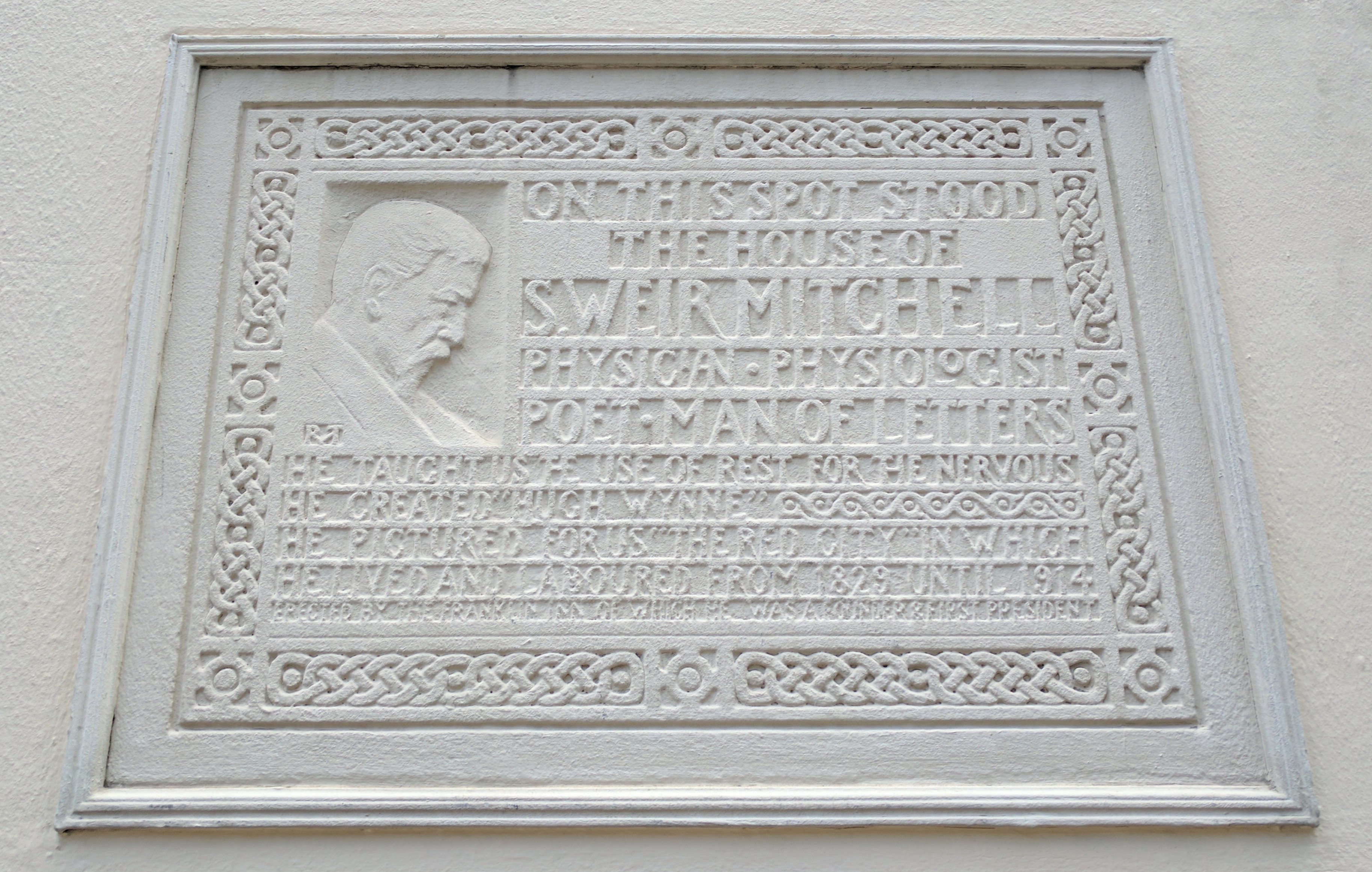

I’m frequently shocked at how much of the world I’ve been missing out on when I occasionally stop to look up. Recently, walking through Center City on Walnut Street for the thousandth time, I happened to turn and catch a glimpse of a plaque on the site of the house of Dr. S. Weir Mitchell, practically indistinguishable from the identically-colored plaster surrounding it. Reading the inscription (“He taught us the use of rest for the nervous. He created ‘Hugh Wynne.’ He pictured for us ‘The Red City’ in which he lived and laboured from 1829 until 1914.”), I felt myself getting angry, and then sad. Silas Weir Mitchell, of the fabled and ineffective “rest cure” for “hysterical” women - “a regimen of forced bed rest, restricted diet, and a combination of massage and electrical muscle stimulation in place of exercise” - lived here. That S. Weir Mitchell, the one who so harmed Charlotte Perkins Gilman that she was inspired to write The Yellow Wallpaper, lived here. How ghastly.

Still agitated by the time I reached home, I undertook an angry Google search. I’m not sure what I was looking for, but what I found was a brilliant article entitled “Crying in the Library” on the blog of the Historical Medical Library of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia. In the piece, researcher Heather Christle describes her experience sorting through Mitchell’s correspondence and diaries in the archive, and how overcome with emotion she became as she read about his own bouts with grief following the death of loved ones. She began to cry (certainly not covered in the Archives Usage Policy) and retreated to collect herself following this empathetic outburst.

I’m familiar with that experience as well. Yes, I have cried in the archives! And, what’s more, according to an informal survey of Facebook connections, I am not the only one. What is it about certain objects and documents that transmit emotions across time and space, leaving us mortals in existential puddles, shaken to the core? And what is it that binds us to these things so that we remember, even years later, exactly which piece of paper made us so miserable?

I’ve laughed in the archives plenty; I’ve also frequently been surprised, confused, and frustrated. But I remember so much more vividly what has made me sad. A friend of mine theorizes that this is because the painful experiences of others elicit a distinct empathetic reaction in us, while we relate to other, less visceral emotions with sympathy. I don’t know how this works, exactly, but I’m always shocked at how affecting archival encounters with the detritus of the day-to-day can be. The question I really want answered is not why it happens, but whether this empathy is a useful tool for researchers and staff who work in the archives.

Scholars are naturally ahead of me on answering this question. Informally, I believe that this ability to personally connect to the people and events of the past can attune me as an archivist and researcher to the more subtle things that we accidentally archive alongside documents - things like power differentials, or bitterly prescient ironies. Drs. Michelle Caswell and Marika Cifor, in their recent Archivaria article “From Human Rights to Feminist Ethics: Radical Empathy in Archives,” advocate for a more relational and community-centered approach to administering archives, one that draws on the practice of radical empathy. They argue that this method acknowledges the human connections that relate us all to one another across time and space:

Radical empathy offers a way to engage with others' experiences that involves discarding the assumption that we share with them the same modal space of belonging in the world. Our conception of empathy is radical in its openness and its call for a willingness to be affected, to be shaped by another's experiences, without blurring the lines between the self and the other. The notion of empathy we are positing assumes that subjects are embodied, that we are inextricably bound to each other through relationships, that we live in complex relations to each other infused with power differences and inequities, and that we care about each other s well-being. (31)

Done carefully, radical empathy can engage archivists and researchers with the records in a potentially healing, inclusive, and more equitable way. If empathetic connection to an archive’s collections, creators, and users is naturally-occurring as well as valuable to the creation of knowledge and community, there’s no reason why it should not be readily facilitated. These acts of care (“affective responsibility”) can start small - even stocking tissues at the reference desk can make a difference, Caswell and Cifor suggest.

Maybe I should carry some with me the next time I’m headed down Walnut Street.