As part of an exercise in analyzing the physical surroundings of Philadelphia’s Independence Seaport Museum, and more specifically the Cruiser Olympia, our Studies in Material Culture class took an hour to walk around the area and observe its “mnemonic landscape.” In practice, this meant that we examined the types and locations of various memorials, monuments, and historical markers that contribute to the neighborhood’s “feel,” and the spatial experience that a tourist or visitor to the area encounters even before they arrive at the museum and board the historic warship. I previously wrote about the museum’s interpretation of the ship (“Olympia in Juxtaposition”), expressing the opinion that Olympia’s contrasts (old/new, officer/sailor, luxury/austerity) are what make it uniquely interesting. My recent excursion among the monuments has convinced me that the same is true of the memorial-but-not-memory-heavy areas of Penn’s Landing and Society Hill. Although the indicators of contrast are less visible to the naked eye - thanks to the efforts of “urban renewal” - they remain embedded in the landscape.

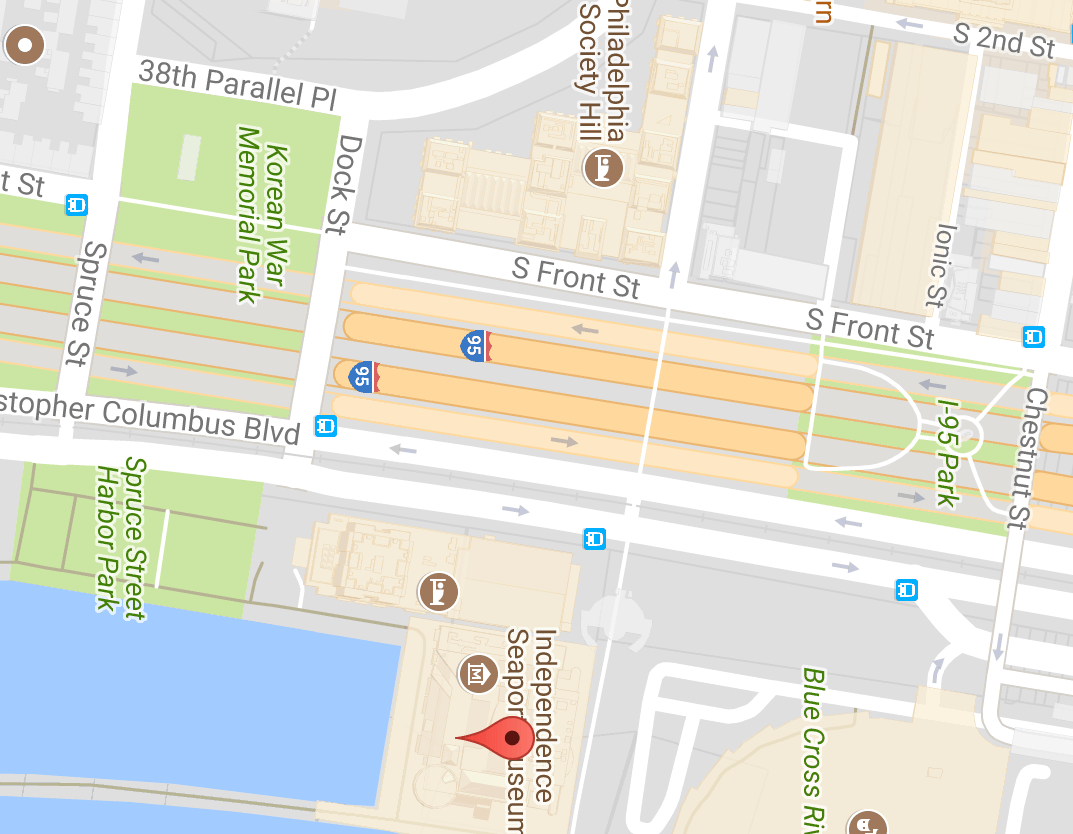

But first: a digression! When I first moved to Philly from Baltimore, slightly over a year ago, the city’s landscape was completely unknown to me. It took me quite a while to adjust to the tribalism of neighborhoods, the relatively flat terrain, the many traffic circles, and the way the numbered streets run north-to-south rather than west-to-east. So, one of the ways that I became more familiar with the city was by using historic maps to orient myself in the research I do here at Temple. This being the case, I was altogether more acquainted with the area that surrounds the Independence Seaport Museum as it looked long ago than how it is in the present (seen below).

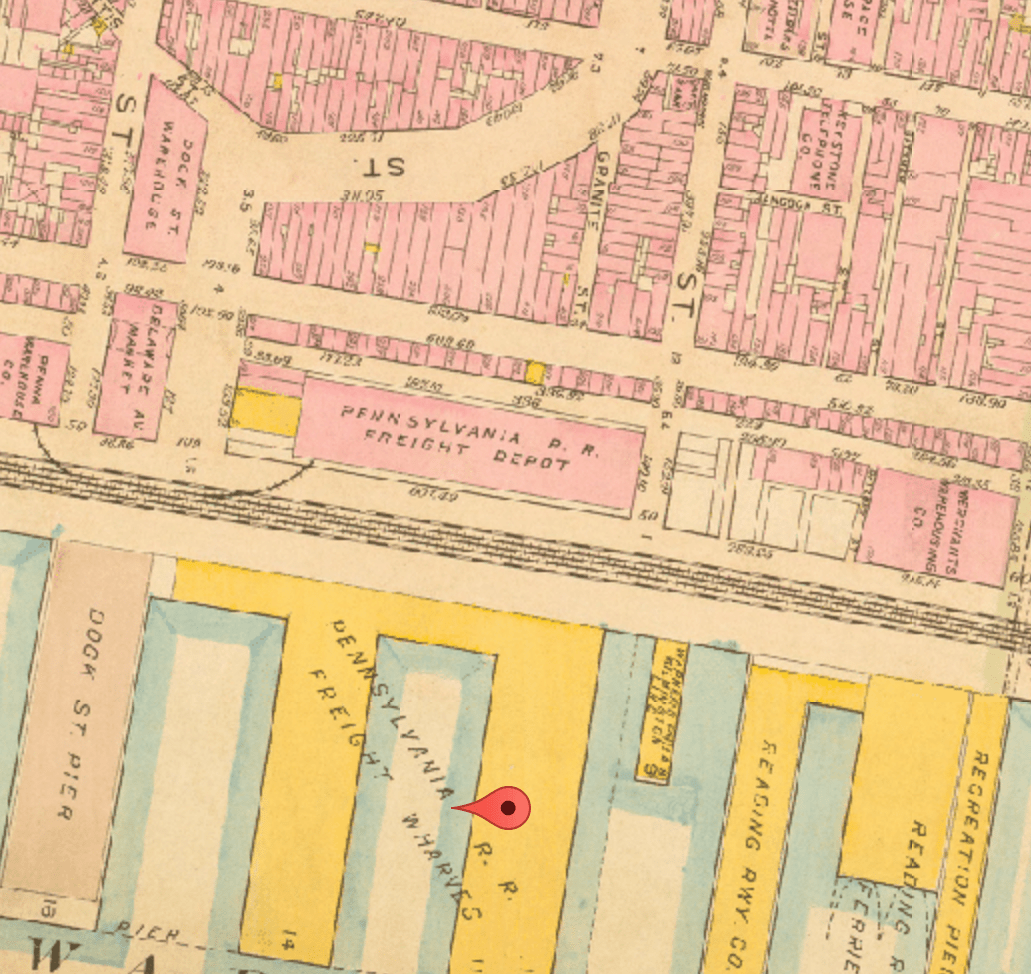

As a historian most interested in the early 20th century, I’m accustomed to consulting the Sanborn fire insurance maps and other, similar atlases to get an idea of an area’s layout. I first used Philadelphia’s maps to investigate the spread of the 1918 Spanish Influenza. The Bromley Atlas below shows that in 1910, the neighborhood where the ISM now stands (marked with a red pin) was bursting with buildings both commercial and residential. It is also apparent that the Pennsylvania Railroad line dividing industrial docks from the rest of the city required a number of freight management facilities. What is not shown on the map is that this area was part of what was colloquially known as “the Bloody Fifth Ward,” an area overcrowded with people and underserved by municipal sewers. The people who lived there - including many African-Americans and European immigrants who worked on the docks and for the railroad - could not afford to live anywhere else.

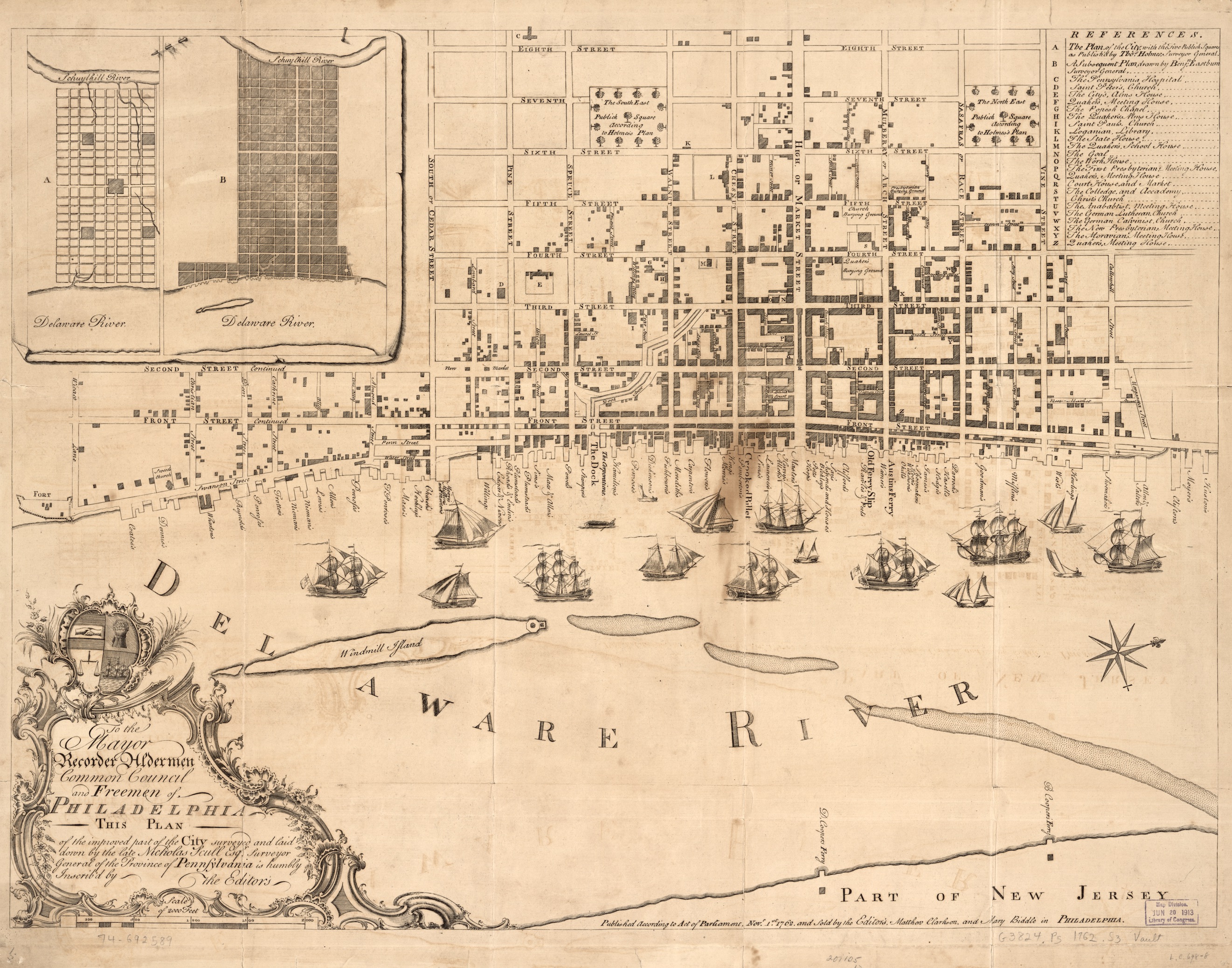

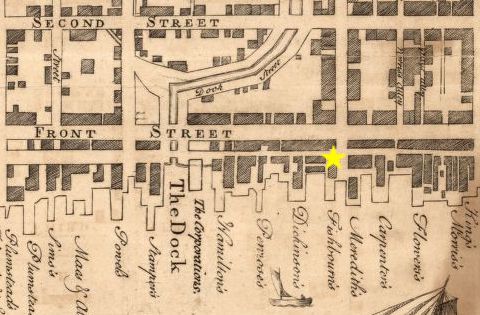

The second map that I used as an explorative tool in this city was the 1762 Nicholas Scull map of Philadelphia, seen above. As I spent my summer fellowship at the American Philosophical Society investigating Benjamin Franklin’s colonial post office ledger book, I was fortunate to spend time in the streets of Old City, gaining a greater understanding of its layout and landmarks. As can be seen, the area that now surrounds the Independence Seaport Museum (indicated by a yellow star), then called the Dock Ward, consisted of a series of commercial wharves and shops. It is also apparent that Dock Street once ran alongside a waterway, a tributary of the Delaware River called Dock Creek. The garbage-choked creek’s pungent effluvium was the impetus for its eventual paving-over in the late 18th century.

By 1957, the area was in shabby shape and deemed “blighted” by developers, who demolished it with the blessing of Mayor Richardson Dilworth and at the behest of the City Planning Commission. Green spaces, and buildings such as the I.M. Pei-designed Society Hill Towers replaced homes and businesses of the working classes. The construction of I-95 soon followed. The transformation from bustling, multicultural waterfront into the newly-rebranded “Society Hill” was complete.

In the present landscape, the green spaces that replaced homes, shops, markets, and rail freight warehouses are filled with memorials and monuments. Primarily, they honor veterans: The Korean War Memorial, Vietnam Veterans Memorial, and Beirut Memorial stand along Dock Street, all constructed in the 1980s or later. The streets are quiet and the parks largely empty. Monuments to the Scottish, Irish, and Italian immigrants who came to Philadelphia dot the vicinity where they might once have lived, but the Dock Ward’s stench and the Bloody Fifth Ward’s commotion are not noted, commemorated, or mourned in Penn’s Landing.

But looking closely, it’s possible for a visitor to pick out vestigial traces of the many lives that came before. Dock Street itself still follows the shape of the tributary that gave it its name and which still runs as a culvert beneath it. Rail lines, long-disused, peek out from in-between the North- and Southbound lanes of Christopher Columbus Boulevard, remnants of the 19th century Pennsylvania Belt Line Railroad. The fact that these scars on the area’s topography are only noticeable because of their incongruity is, ironically, the only visible evidence of the biggest scar of all: the demolition and displacement of the contents of a long-storied city neighborhood.

This particular scar, however, does have a monument: the “Phoenix Rising” sculpture in honor of Mayor Dilworth and his legacy of Society Hill “renewal.” The sculpture, dedicated in 1982, was once situated in the heart of the city at Dilworth Plaza. In 2013, though, the sculpture was relocated to the intersection of 2nd and Dock Streets, in front of the Society Hill Towers, where, like the historic landscapes of this portion of the city, it is barely noticeable. It is certainly not particularly memorable.

If the mnemonic power of any of these landscapes depends on their juxtaposition within the context of what came before, I am of the opinion that the area of memorials surrounding the Independence Seaport Museum fails the test. In erasing so many traces of the urban maritime past from the area, the redevelopers of the 1950s-1970s have made it feel like it never happened, detracting from the rich potential of the waterfront to engage both locals and visitors in imagining the connections between the present and the past.