Back in 1892, art exhibitions were not held for the general public. Art galleries were considered suitable only for the better classes, like art students and connoisseurs, and to this point, they charged admission and kept limited hours. So it shocked New York City when, on a hot Monday night in June, an exhibition of about 100 works of contemporary art opened its doors on Allen Street on the Lower East Side to the working people of the neighborhood- for FREE.

Suspicion on all sides

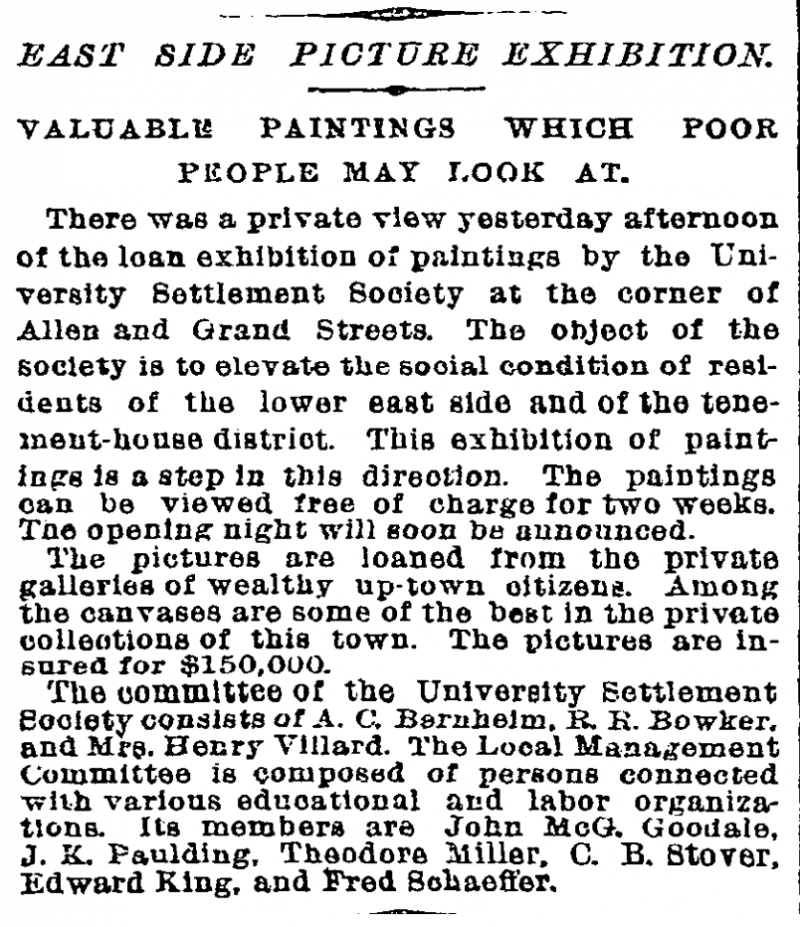

The New York Times announcement of the upcoming exhibition dripped with disdain, playing up the foolishness of the gesture (valuable paintings which poor people may look at!) by underscoring the monetary value of the paintings to be exhibited; notice the insurance value listed in the article.

Meanwhile, the labor newspapers of the city criticized the exhibition on different grounds. A prominent neighborhood socialist was noted to have objected: "The robbed and the robbers cannot sincerely fraternize, especially when the robber comes asking the robbed to accept as a favor a few crumbs from the feast which is the creation of the latter." [1]

A happy result

And yet the exhibition was a smashing success. It attracted 36,095 visitors in a forty-one day run, which in 1892 would have amounted to roughly 17% of the city's population living below Fourteenth Street. [1] The social organizations that arranged the exhibition, the East Side Art League and the University Settlement Society, continued to hold it annually for the next five years. By that time the ideals of cultural democracy had begun to spread among the leaders of New York City arts and cultural institutions.

What makes arts and culture initiatives stand out?

Nowadays thousands of organizations abound with mission statements that do not vary greatly from the aims of those early modern philanthropists: that of "interesting and instructing those to whom poverty forbids the pleasures of art." [2] What makes any of them stand out? Some might claim their longevity, others their creativity, publicity, or financial health.

The East Side Art Exhibition was not a financially sustainable venture. It was an experiment that turned out successful- even converting the neighborhood socialists if the testimony of labor activist and University Settlement Society committee member Edward King is to be believed. [1] So what made this particular idea impactful? In its limited run, it introduced new ideas, based on careful audience research, into the world of cultural philanthropy in the United States that remain valued today:

- The exhibition was open in the evenings from 7-10:30pm on weekdays, and on Sunday afternoons.

- Admission was free.

- Docents stood by to offer assistance, as if it were an uptown gallery.

- Visitors were asked to vote on their favorite paintings.

- A descriptive catalogue was distributed in both English and Hebrew to accommodate the area's residents.

Learning from the past

The East Side Art Exhibition didn't upend the social stratification of the Gilded Age. It didn't dismantle the capitalist system that made it necessary for laborers of 1892 to work an average of 60 hours a week or more to support their families. [3] It had no effect whatsoever on miserable, dangerous living or working conditions. What it did help do was humanize New York City's working people in the eyes of the wealthy, conservative, and skeptical, while treating its visitors with dignity and welcome.

I'm not sure that this is a grand enough mission for the arts and cultural nonprofits of today. It's not 1892, but this country is facing what some observers have called the "New Gilded Age". At what point will we move beyond "providing access" and "promoting education"? When will we acknowledge that the system of inequality feeds itself, and work to change it?

Works Cited

- A.C. Bernheim, “Results of Picture-Exhibitions in Lower New York,” The Forum (July 1895), 610–13.

- "The Fine Arts: The East Side Loan Exhibition," The Critic, 20 no. 540 (June 25, 1892).

- Robert Whaples, "Hours of Work in U.S. History," The Economic History Association, EH.net, https://eh.net/encyclopedia/hours-of-work-in-u-s-history/

This article originally appeared in a slightly different format on the Steemit platform and carried this tagline: "100% of the SBD rewards from this #explore1918 post will support the Philadelphia History Initiative @phillyhistory. This crypto-experiment conducted by graduate courses at Temple University's Center for Public History and MLA Program is exploring history and empowering education. To learn more click here." It is no longer accruing Steem cryptocurrency.